Smart-shoring

Here is how to achieve a true manufacturing renaissance with greenfield innovations driven by x-shoring.

In my previous post Second Chance, I described why the time is ripe for the USA to start its manufacturing renaissance with greenfield manufacturing innovation as a part of the x-shoring trend. In this post, I shed light on how to achieve this renaissance, explain key concepts, and give some examples.

One of the most outstanding examples of intelligent manufacturing of our time is Tesla. To put this into perspective, as of September 2023, Tesla has a market cap of $675b, three times that of Toyota. Also, Tesla has an operating margin of 11.21% which beats Toyota’s operating margin of 9.87%, while, ironically, Toyota is still considered the north star of efficiency by many experts.

As Tesla epitomized, intelligent manufacturing is about creating “Competitive Advantage” with a mix of innovations involving design, engineering, manufacturing, supply chain, customer experience, etc. On the other hand, I don’t see any intelligence in buying and implementing commoditized efficiency technologies over the same old business models, operating models, and old factories. Yes, I agree that efficiency technologies and lean are required, but these are bolt-on commodities.

Due to the irresistible ease and attractiveness of buzz-word marketing, tech vendors pitch almost anything, mostly commoditized efficiency technologies, under labels such as intelligent manufacturing, smart manufacturing, or industry 4.0. On the other hand, there is the sacred religion of Lean and its faithful cult. The sacredness of lean and mass parroting of the technology buzz-word narratives provide an intellectual short circuit and political safety to the super busy executives trying to survive the quarter.

A similar myopia is currently happening with the x-shoring trend. In my previous post, Second Chance, I argued that the x-shoring trend is an excellent chance for US manufacturing to create the nation’s industrial renaissance with greenfield factories. But, this renaissance entails radical factory designs wrapped with other innovations. Because more-of-the-same-old factory concepts rebuilt with more expensive gear and more complex IT are prone to fail in competition in a high input cost context. Therefore, it is critical to have a strategic look at manufacturing with a fresh perspective and deeper intelligence that outsmarts the competitors. This change in perspective is an excellent start to do smart-shoring and avoid dumb-shoring.

Before introducing more prescriptive strategies, let’s set up four foundational premises.

As long as a manufacturer is a price taker, efficiency gains are profitable until the next best competitor adopts efficiency solutions to a similar effect. Thus, efficiency gains pass to customers as lower prices. In today’s hyper-connected and fast-paced world, efficiency solutions disseminate quickly and become equally available to competing manufacturers. Also, most industrial buyers catalyze the dissemination of efficiency solutions among their suppliers.

Efficiency gains approximate a hard limit and are achieved with diminishing returns and increasing complexity. In contrast, the topline can grow infinitely to the extent of the pricing power which is a function of competitive advantage.

Competitive advantage lasts significantly longer (decades) than relative efficiency (months). See Michael Porter’s explanation here.

Competitive advantage is different than efficiency, agility, and flexibility, which are capabilities, not advantages. Competitive advantage is relative, exogenous, and structural, exemplified by network effects, switching costs, learning curve, predatory capacity, etc.

Advantage is relative, exogenous, and structural.

Now, let’s talk about some basic strategies.

Complex innovations

There is an abundance of sustaining innovations that add dimensions and enhance performance for a given value framework. Sustaining innovations in isolation can be copied relatively quickly, but a large number of sustaining innovations sprinkled across the value chain becomes too complex to copy. Most business model innovations go into this category of complex innovations as they hit several aspects of the business at once, typically in ways individual components of the new business model don’t make sense or seem outright stupid in isolation.

i.e. Mass customization + programmable manufacturing processes + micro factories + crowdsourced supply + open source design + direct-to-customer (see Local Motors, eGO)

Complex organic proprietary know-how

The idea here is to create a unique set of genes, then organically grow and improve in time. Imitators cannot copy genes; even if they can, they will be behind your growth & learning curve.

For example, there is still no other Zara although the Zara model has been successful for decades and was studied inside out by thousands of people. Similarly, Toyota is well-studied, but there is no other Toyota in its game, despite Toyota itself published the correct way to implement their model. It is hard to copy complex organic know-how because it takes copying the philosophy, culture, and organization without undergoing the same evolutionary path. There is no such shortcut.

Manufacturing is a pure know-how business after all. A typical manufacturer uses hundreds of off-the-shelf software, buys machines, tools, and parts, and hires people. What remains as core manufacturing seems to be pushing buttons, changing tools, maintaining assets, tracking trucks, moving carts on the shop floor, etc. But what ultimately counts is the know-how to orchestrate all these activities in the best possible way. Given this orchestration know-how, everything else is a bolt-on that is equally available to competitors unless protected as proprietary. Therefore, investing in learning, knowledge management, internal innovation, hiring - growing - retaining people in a stable workplace, and accumulating institutional know-how is far more competitive than buying the best machine and software in an otherwise context.

Network Effects

In the U.S., you could have a meeting of tooling engineers and I'm not sure we could fill the room. In China, you could fill multiple football fields.

Apple CEO, Tim Cook

X-shoring is typically considered as units of individual sites being moved. But manufacturing occurs within an ecosystem, and x-shoring a site into a weak ecosystem is a significant disadvantage for the site.

Alternatively, it might be faster to focus x-shoring to the peripheries and critical nodes of the networks and ease skills bottlenecks with pragmatic policies. This requires simple and practical industrial policies executed at the speed of business, not at the speed of government.

I will write more on this later.

Disruptive innovations

Disruptive innovations distort or even transpose the established value-creation framework of the industry and start creeping into the market from segments overlooked by the incumbents. So, it is like a virus that evades your immune system for a long time, showing very mild symptoms not to alert you and nudge you to deny the threat until it is too late.

Given this definition of disruptive innovation, 99.99% of all the so-called disruptive innovations such as predictive maintenance, real-time analytics, and robotic palletizing are not disruptive at all.

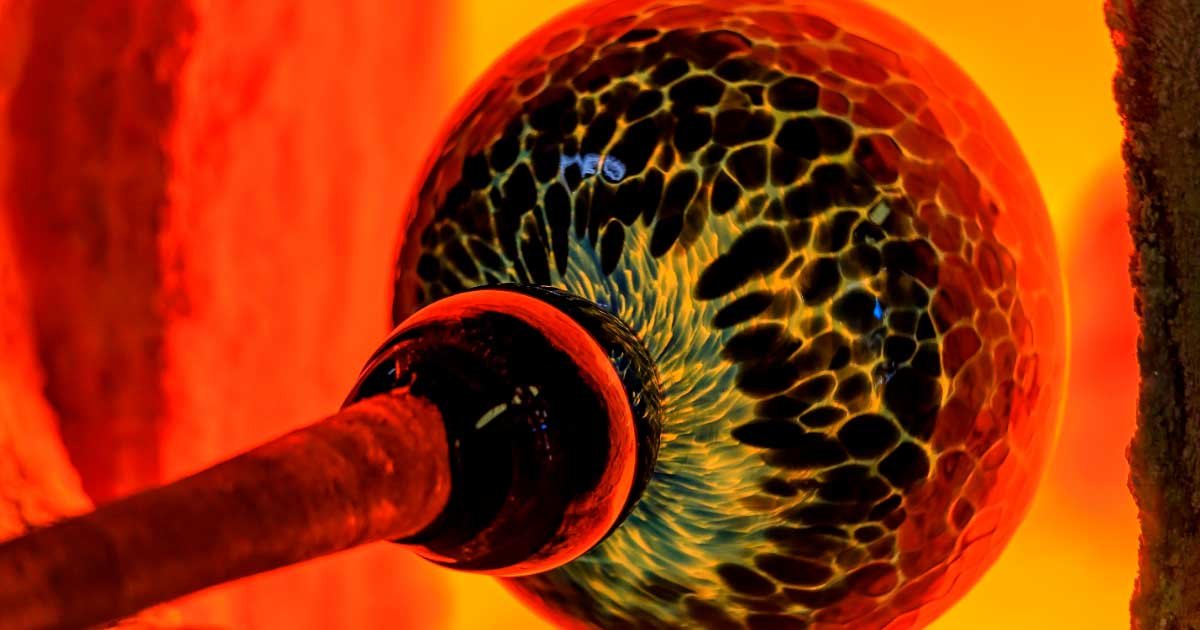

There are plenty of disruptive innovations in the market facing the end of the value chain from the sales, product, digitalization, and servicification angles. But good examples of pure-play manufacturing disruptions are pretty limited. Take for example the giga press of Tesla which is a significant manufacturing disruption in the auto industry and the JIT revolution of 70s & 80s.

In my previous posts, I shared some great examples to work on for future manufacturing disruptions.

Contact me to dive deep into more concrete details of formulating true disruption.

© Saip Eren Yilmaz, 2023